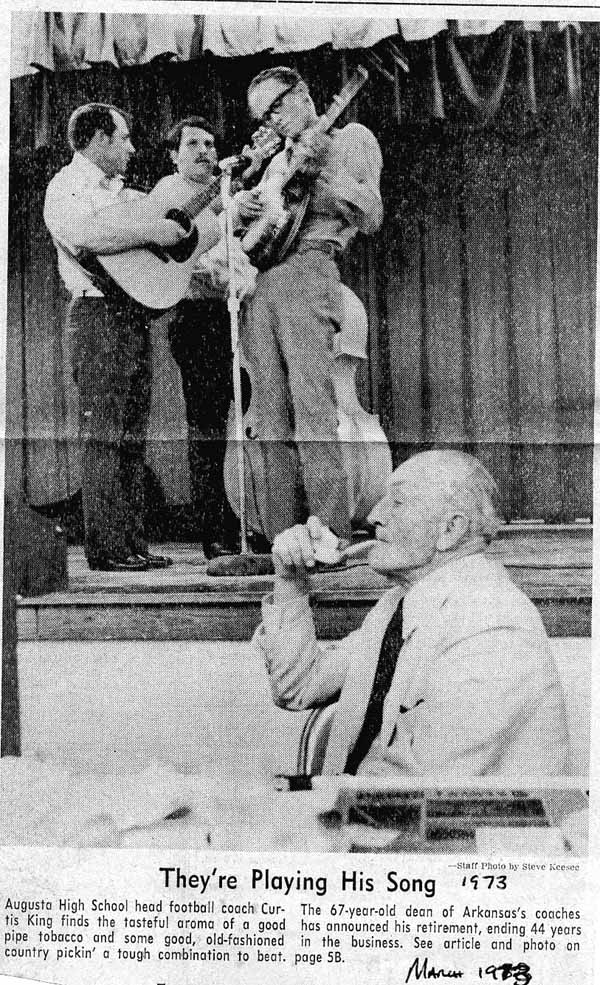

Arkansas Gazette, Sunday, March 18, 1973

Curtis King, who died in 1980, was the first high school coach elected to the Arkansas Hall of Fame. He's well remembered now as a successful and colorful coach and math teacher.

He's best known for coaching the Augusta Red Devils for 29 years, from 1944 to 1973. His record there was 182 wins, 105 losses and 12 ties. His winning percentage of .608 is impressive, especially considering that teams from the larger towns of Searcy, Newport and Batesville were opponents for years.

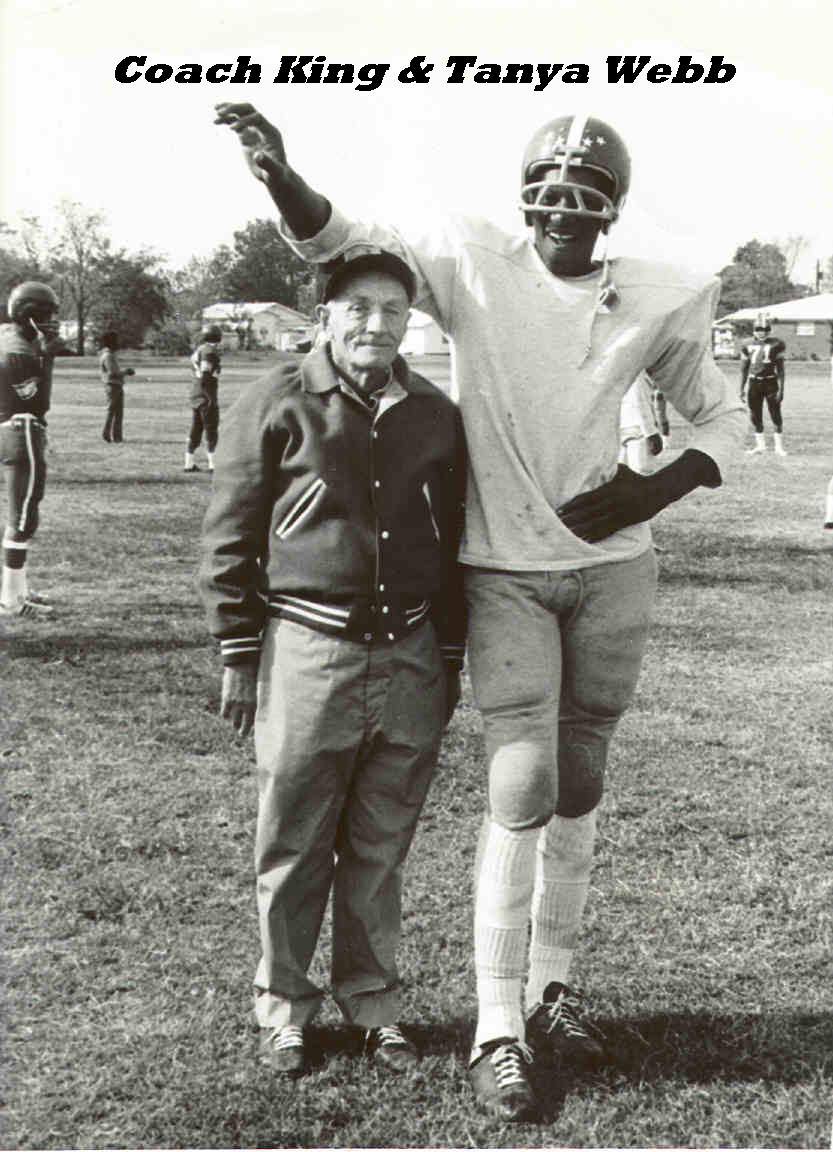

Billy Ray Smith, Augusta's most famous athlete, recently described coach King. "He was probably the finest high school coach in the state. He could do more with less material than anyone," Smith said. "He knew how to handle his players."

Smith played four years for the Arkansas Razorbacks in 1953-57, and then for 14 years as a professional player. He was an all-pro tackle with the Baltimore Colts.

When a heart problem forced King to retire from coaching in 1973, Smith flew in from Dallas to attend a banquet in King's honor in Mountain View. He told 250 guests, "Coach King has been the greatest influence on my life. He never gave up on me."

He continued, "I was just a big old dumb smart-aleck kid at Augusta. I was one of those kids you couldn't teach a thing. You had to beat everything into me. And Coach King did. ... He cared for and loved me. I took up a lot of his time and gave him a lot of headaches, but he stuck with me. He was like that to all the kids. He loved us like we were his own."

King had promised his wife, Nell, that he wouldn't speak at the banquet, but he couldn't resist a little reminiscing. "I've never gone anywhere and said nothing," he said. "Four and a half decades ago, I started my coaching career in a one-room school- house at Mountain View. It was 1929.1 had a brand-new Model A (Ford); a pretty young wife; six fox hounds; and $17.50 in my pocket. Tonight, 44 years later, I return with a secondhand car and a worn-out woman, my dogs are dead, and I'm overdrawn at the bank."

Jerry King, the coach's son, says his father grew up playing baseball and basketball in Mountain View. "They didn't have football at their high School then," he said. A newspaper clipping says Curtis played at Arkansas (now Lyon) College, but Jerry thinks his father played at Jonesboro Baptist College.

Wherever he played, apparently he didn't play much football. He got his training as a football coach as assistant to Beebe coach Ambrose "Bro" Erwin, who had some great teams in those years, the late 1930s and early '40s.

At the Mountain View banquet, Erwin described King's work: "He had a better relationship with the players than I did. I knew right from the start that Curt was going to make an excellent coach. He was stern yet he was fair with the boys. He was more of a father image to them. They respected him."

When Augusta was looking for a coach in 1944, Erwin recommended King, who was in Tennessee working construction jobs. "It didn't take us long to find him, and I guess it took Curt even a shorter time to accept the job," Erwin said.

Early on, King coached everything: junior and senior high boys' football and basketball, junior and senior high girls' basketball and track. He also taught five math classes, drove a school bus and was a general clean-up man.

In the 15 years that he coached basketball, he gave it the same intensity that he brought to football. A rival coach said King would try to get a psychological advantage. "He would list his players two or three inches shorter than they were, and he was the best at baiting officials," the coach said.

Jerry King recalls a run-in his father had with a referee. "The referee told Dad, 'I'm not going to give you a technical foul for coming onto the court, but I'm going to give you one for every step it takes for you to get back to the bench.' Dad didn't take a step but whistled to his players, and they carried him back."

Jerry says his father may have enjoyed teaching even more than coaching. "His father and grandfather had been teachers," Jerry said, "and Dad began to teach long before he got a degree."

Curtis King once called himself "the longest-term student in the United States." He started college in 1927 and finished in 1950, 23 years later. He would teach and coach in the school year and attend Arkansas College in the summer.

Glen Pace of Searcy remembers being in classes with King around 1949-50. "He was a very colorful, high-profile character who was well known at the time," Pace recalled. "He spoke out in class, mostly with wit and humor."

In a female professor's Bible class one day, the subject was divorce. A student wanted to know about the spiritual status of Dick Powell, the actor who had grown up in Mountain View and was then married to actress Joan Blondell, his fifth wife. The teacher's response that she hoped Powell was happy with his wife brought a "Which one?" from King, Pace said.

At a sports banquet in Searcy, Pace, who was to introduce King, got a flowery build-up as a preacher of known ability. As he rose to speak, King said, "I taught Glen all he knows about the Bible."

He often turned humor on himself. "Someone told King that over the years his features had change so little," Pace said. "He looked the person straight in the eye and sail 'Mummies don't change.'"

Wit in the classroom

He was a natural as a teacher Although small (5 feet 7 inches an about 160 pounds), he had a booming voice and a presence that demanded respect. Former students say he'd throw an eraser or a piece of chalk at a recalcitrant student

He might have the class sing the math principles he was teaching.

He used the Bible to back up his quest for student achievement. A favorite statement was "Woe be unto him that does not get his homework, for there shall be weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth."

To emphasize the pi-r-squared mathematical formula for determining a circle's circumference, he had his wife bake a special pie. He brought it to class covered and asked a student what shape pie was. When the answer was "round," he took a towel off his square-shaped pie as a reminder: "Pie are squared."

He was known to kneel beside the desk of an unprepared student and pray, "0, Lord, send your great angels and put some brains in this poor nincompoop's head."

Billy Ray Smith remembers, "He'd tear you up in class if you didn't have your lesson." But he and other former Augusta athletes all say King was a great teacher.

Bobby Pearrow, who played as a 135-pound guard in the early '50s, said, "He went to great limits to help. He gave me a good math background, and that benefited me more than any other subject." King had such an influence on Pearrow, in fact, that he and his wife named their son Curtis after the coach.

Smith and his cousin Boots Simmons, who also played tackle for Augusta, told about King making them come to the front of the class for a spanking with a book. "He wouldn't hurt you much, but he could sure scare you," Smith said.

In 1978, Suzy Potter Lawler, who played basketball at Augusta in the late '40s, wrote, "He not only taught us to work math problems and be good in sports ... he taught us how to cope; how to get along in life; how to respect and be respected; how to live, and when necessary, to fight to live with dignity"

Shrewd strategy

Jerry King said his dad liked to come up with trick plays. One was the "lonesome end": an end lining up close to the sideline, where the defense might overlook him. Another was the "covey" play, designed to hide the ball on kickoff. "Everybody would gather around the ball and then burst out," Jerry said.

To beat Alma in the second overtime of the 1969 playoffs, King had his offense line up in the almost forgotten single-wing offense. With quarterback Mark Miller at tail-back, Augusta marched down the field to score and win, 20-14.

In King's early years at Augusta, the football team had few players; one year there were only 16, Smith said. King would blow his whistle quickly in practice to avoid injuries. One day there was a big pile-up, but no whistle. Surprised players, looking toward King, saw ashes flying from his pipe.

Almost every one of Augusta's 2,500 residents knows about the time that King pulled his team off the field before a 1949 game in Pocahontas. A fellow coach had tipped him off that the home team was planning to use a white ball with no stripes because it would blend in with their white uniforms.

King had a blue football and told the officials that if Pocahontas used a white ball during the first half, the Blue Devil's should get to use the blue one in the second. Rival coach Cob Fowler didn't agree.

"I was the captain," Boots Simmons said. "When we met at midfield I learned the white ball was to be used. I gave Coach a signal, and he told us to get on the bus. People threw rocks at the bus as we left."

Pocahontas was awarded a 1-0 forfeit, but on appeal the Arkansas Activities Association reversed the decision. The 1-0 victory was part of a 10-1 season for Augusta.

"Dad told me later it was an extremely hard decision for him to leave the game," Jerry said. "He said it was emotional to so many young people from both sides, their fans (about 6,000 had gathered) and communities. He also mentioned the 'Do Right' rule."

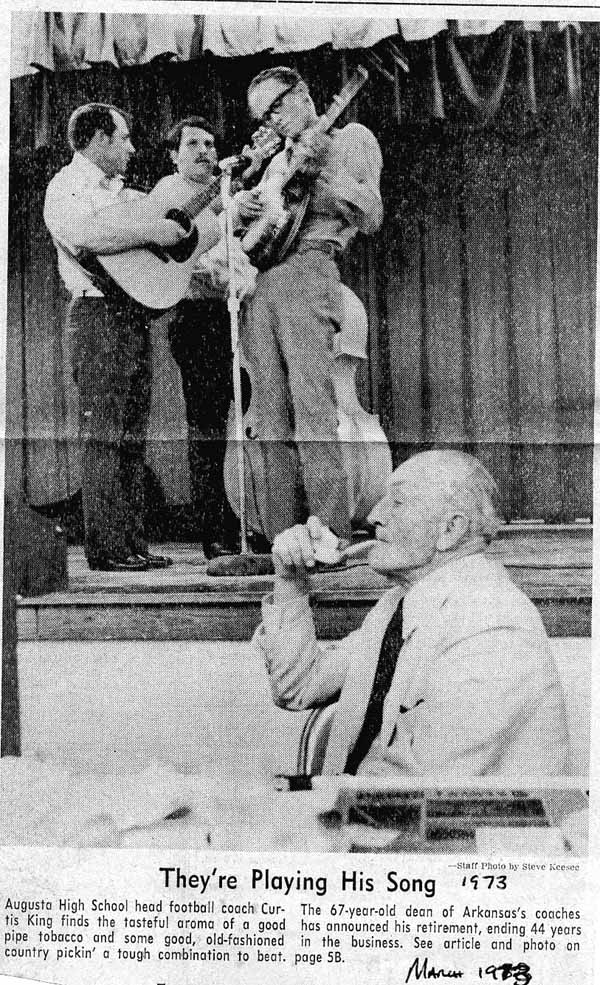

The closest King got to an undefeated season came in '69, when he had 35 players and two assistants, George Jones and John Matlock. The team beat everyone, including Little Rock Parkview, in the regular season. After beating Piggott and Alma in the playoffs, they were 13-0. McGhee stopped them in the championship game. King won the Lowell Manning Award as the outstanding coach in Arkansas for that memorable season.

Over the years, he got coaching offers from bigger schools, even Arkansas State University. Jerry said his father told ASU, "We're really good friends, but if I came and lost, you might fire me in a couple of years. Let's stay friends."

In July 1966, Augusta held an appreciation day for Coach King. Gifts included a color television set, golf clubs, an electric golf cart and a plaque of appreciation. King responded, "I hope a voting majority of the school board is here tonight. If I had known I was that good, I would have asked for a raise a long time ago."

John Eldridge, who played quarterback just before King became coach and whose two sons played for King, said the coach had the ability to push players beyond their limits, but loved them. "He told me, IÕll chew a player out, but before the practice or game is over, IÕll compliment him and he'll leave feeling good," Eldridge said.

Eldridge's father offered King a better-paying job with the family farm-equipment business. "He turned it down, saying he was just interested in the kids and Augusta," Eldridge said.

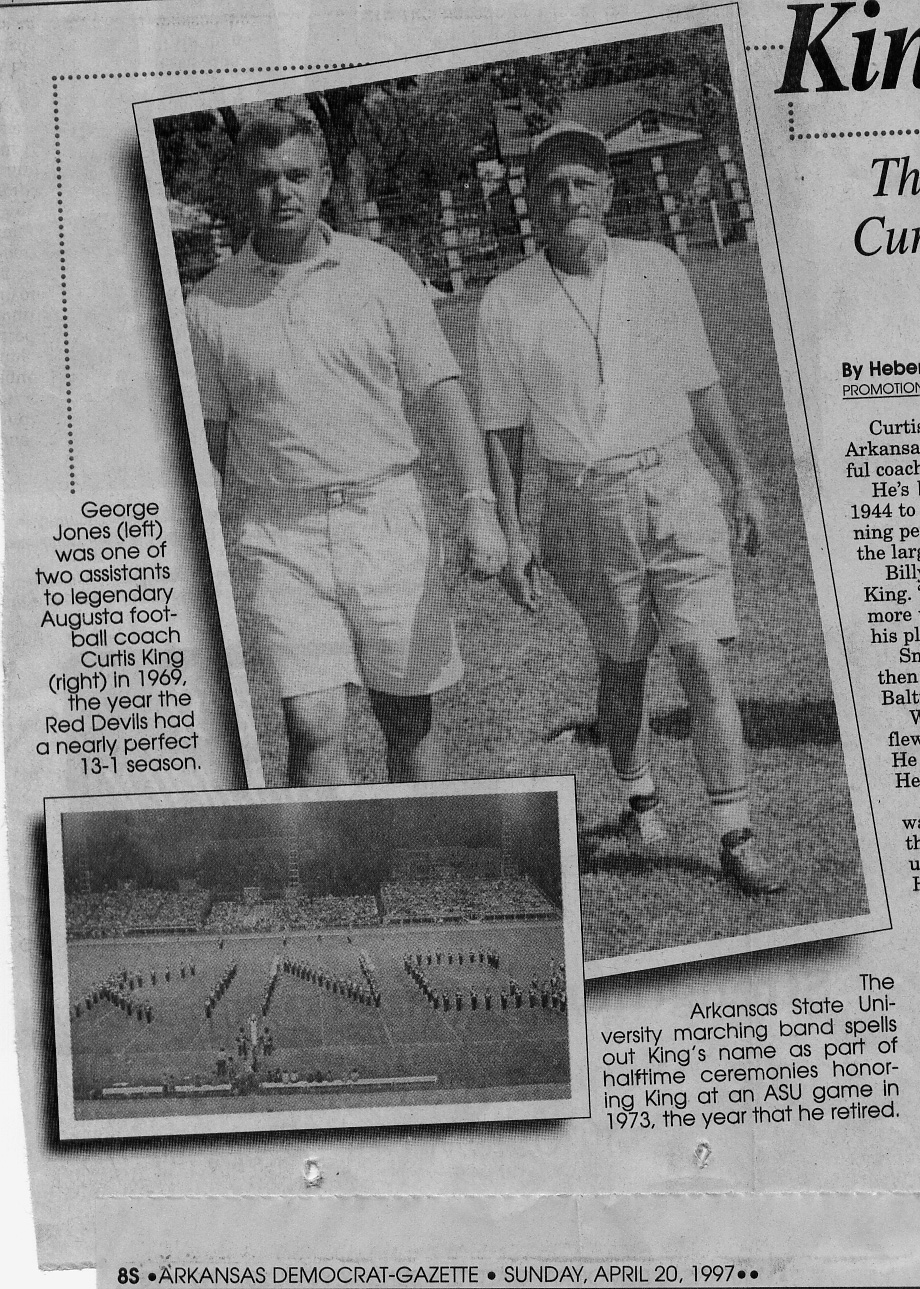

After King's heart attack in the spring of '72, Eldridge advised him not to coach. "He said he had a team of seniors and all he'd have to do in practice was to throw out a ball," Eldridge said. "He said he'd control himself during games."

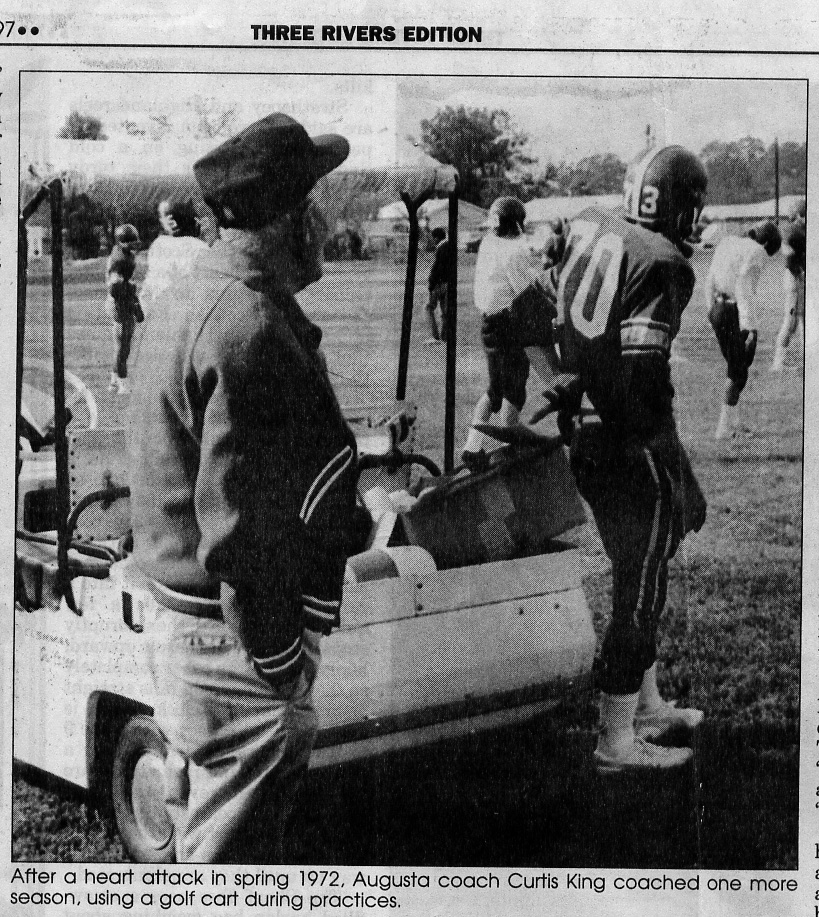

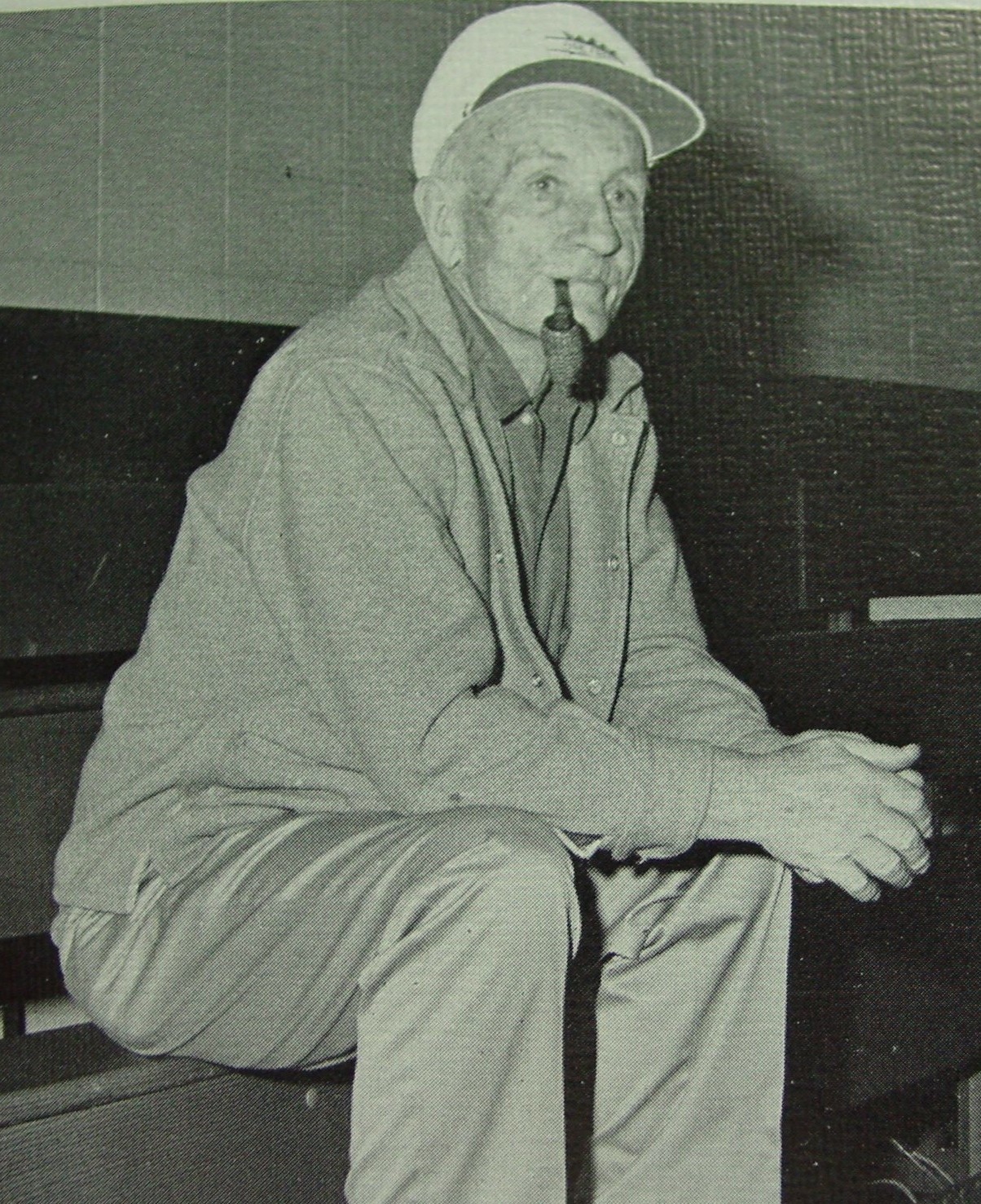

Lonnie May played on King's last team in 1972. the year King used a golf cart in practice and a chair at games because of the heart attack. But he hadn't lost any fire.

"He could get it out of you," May said. "He would make everybody mad at the beginning of practice, but everybody would be happy at the end. He'd slide up behind you and drop-kick you with the side of his foot or he'd grab you by the face mask, but he made you like him."

After he retired in 1973. ASU honored King during halftime of its September 8 game. The band spelled out "KING" and "AAA" and played the tune "King of the Road."

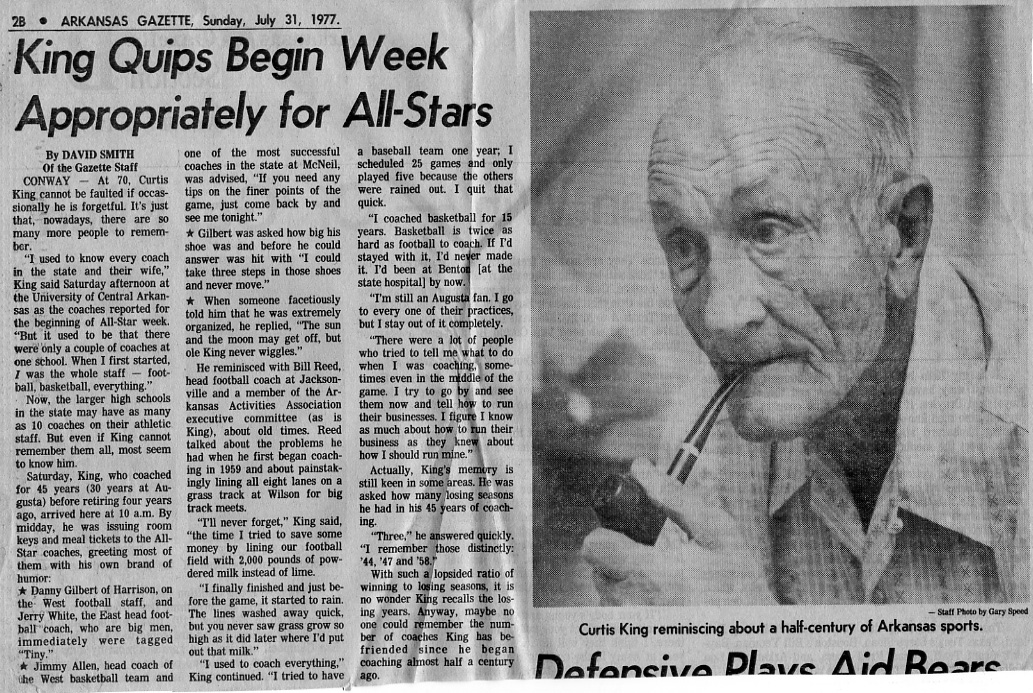

King had open-heart surgery in 1977 and had to miss the annual football and basketball all-star games sponsored by the Arkansas High School Coaches Association (AHSCA). He'd helped start the association and the games; in retirement he still helped football players get ready for the August games. He would greet the athletes as they arrived, give them a humorous talk and then serve as "house mother" for the week. A sports- writer described him as "a combination of Popeye and my grandfather. But to players like Billy Ray Smith and hundreds of others ... he was more like Superman."

In the spring of 1980, King was named to the Arkansas Hall of Fame, and the Curt King Award was established by the AHSCA. The latter would honor, each year, a coach who was fair and impartial with his players and concerned about their total welfare, and who maintained friendly relations with his peers and assisted in the professional growth of others; all things King was known for.

King liked to help other coaches and was still doing that hours before he died at a Searcy hospital in October 1980. "The night he died, I went to see him," said John Prock, then head football coach at Harding. "He was a good friend, and he talked seriously about football." Another friend who visited that night was "Bro" Erwin. Jerry said, "I sensed they wanted to say goodbye, so I left the room and stood by the doorway. The last words I heard between these two giants of high school athletics and education were 'I love you, too, Curt.' I finally realized why my parents named me Jerry Ambrose King."

The funeral was held at King Field, named for the coach. The stands were packed in the town where he was a beloved legend. If King could have spoken, he might have repeated words he spoke in 1970: "I never had enough sense to do anything else. Any idiot can coach. You only have to do three things to be able to coach today; drive a bus, clean out a commode and repair equipment."

Rex Nelson writes about King of Coaches, January 2014.

Coach King with team in Fall of 1958

Coach King with team in Fall of 1963

Return to Main Index

add Rex N 1/8/14